Foreign direct investment (FDI) flows into Africa are expected to pick up in 2023 – with mining and gas projects leading the way – following a lacklustre investment climate during 2022.

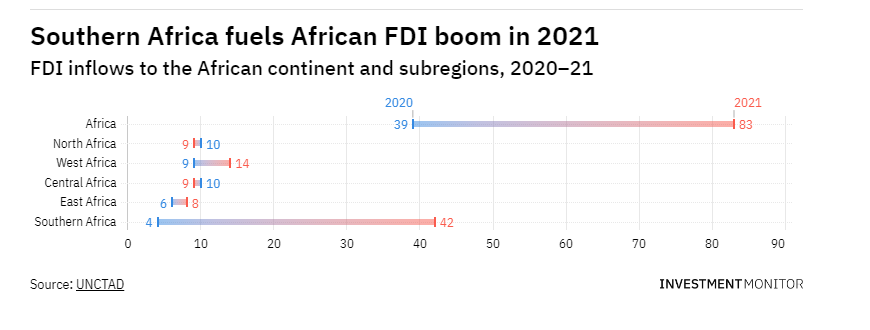

In 2021, the continent saw FDI rebound strongly after the sharp decline in 2020 prompted by the Covid-19 pandemic – FDI to African countries hit a record $83bn in 2021, according to the UN Conference on Trade and Development (UNCTAD) World Investment Report 2022. This was more than double the amount reported in 2020.

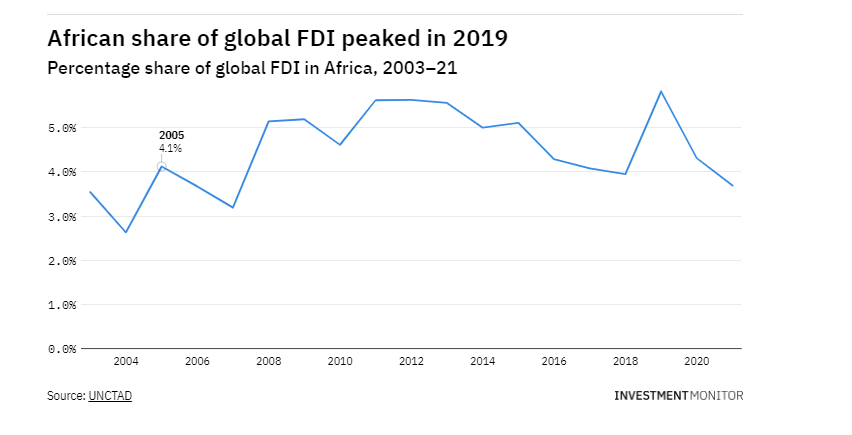

However, despite the robust growth during 2021, investment flows to Africa accounted for only 5.2% of global FDI, up from 4.1% in 2020. While most Africa countries saw a moderate rise in FDI in 2021, about 45% of the total was due to one intra-firm financial transaction in South Africa (a share exchange between Naspers, the South African internet and technology company, and Prosus, the global investment group, in the third quarter of 2021).

Furthermore, although the official FDI statistics for 2022 are not available yet, experts say that anecdotal evidence indicates that inflows during 2022 were weaker than 2021 in the wake of the deteriorating global economic environment and security situation.

“Anecdotally, FDI inflows into Africa were a bit disappointing during 2022,” says Isaac Matshego, an economist at Nedbank, which is based in South Africa. “Global conditions were less favourable and financing conditions were tighter amid rising interest rates globally. I expect FDI into the region to pick up during 2023, but the global environment is certainly less favourable than before the pandemic. The disruption to global supply chains is not helping the situation and the international flow of capital is under pressure.

“However, I think the limited supply of Russian oil and gas to Europe is leading European investors to look at Africa more closely. We could start to see further exploration in oil and gas in Namibia and the liquefied natural gas [LNG] projects in Mozambique – stalled because of security concerns there – could resume.”

Three massive LNG projects with a combined investment of $55bn are planned for Mozambique, although some estimates put the total investment as high as $100bn. These are huge sums compared with the size of the Mozambican economy ($18bn in 2022).

Of the three projects, two are big onshore affairs: one led by TotalEnergies, the French oil and gas major, and known as the Mozambique LNG project, and another led by US-based ExxonMobil, and known as the Rovuma LNG project. The third, smaller project – known as Coral South – is led by Eni, the Italian oil and gas major, which plans to invest a total of $7bn. It differs from the other two bigger projects as it involves constructing a floating liquefaction unit connected to six subsea wells.

Big oil and gas discoveries in Namibia

During 2022, TotalEnergies and Shell, the British multinational oil and gas company, announced that they had made “significant” oil and gas discoveries off the coast of Namibia, which experts say are likely to run into billions of barrels of oil equivalent. The companies are in the process of drilling their second and third wells and were expected to have completed the appraisals and have better estimated figures by the end of 2022.

Moreover, economists think that Africa will eventually receive a great deal more foreign investment in the mining sector in light of the global energy transition. The continent is home to around 30% of the world’s mineral reserves, according to the UN. In 2019, Africa only produced around 5.5% of the world’s minerals and its global share was valued at $406bn that year, according to the World Mining Congress.

Africa has some of the world’s biggest deposits of minerals essential to the energy transition: nickel, cobalt, graphite, lithium and rare earth elements. For example, it accounts for around 80% of the world’s total supply of platinum, 50% of manganese and two-thirds of cobalt. The continent also holds 40% of the world’s gold reserves and up to 90% of its chromium. Guinea alone produces more than 20% of the world’s bauxite used in aluminium production.

Renewable energy investment in Africa trails far behind the rest of the world, but economists believe it could get better in the future. Despite rapidly growing electricity demand and improving policy frameworks, only $2.6bn of capital was deployed for new wind, solar, geothermal or other renewable power-generating projects in the region in 2021, the lowest in 11 years. In 2021, the continent accounted for only 0.6% of the $434bn invested in renewables worldwide.

Clean energy investment in Africa is highly concentrated in a handful of markets. South Africa, Egypt, Morocco and Kenya have accounted for almost three-quarters of all renewable energy asset investment since 2010 with a total of $46bn. All other African countries have secured only $16bn over that time.

Africa’s green and blue economies could attract huge investment

Experts says that improving renewables investment in Africa requires a new level of collaboration between the private and public sectors in order to identify viable clean energy projects and to bring more private financing and public support to them. The number of international projects in renewables in Africa climbed to 71 in 2021, including a $20bn project to provide solar and wind energy from Morocco to the UK via 3,800m of subsea cables.

“For long-term prospects, the African continent has great potential to attract international investment in the green and blue economies, as well as infrastructure,” says James Zhan, senior director, investment and enterprise, at UNCTAD. “A challenge is to further improve the investment climate and strengthen Africa’s capacity to absorb such sustainable investment.”

Green economy strategies tend to focus on the sectors of energy, transport, sometimes agriculture and forestry, while the blue economy focuses on fisheries sectors and marine and coastal resources.

During 2021, in terms of sub-regions, Southern Africa, East Africa and West Africa saw their investment flows rise, while those to Central Africa remained flat and North Africa registered a decline. New project announcements in South Africa included a $4.6bn clean energy project finance deal sponsored by Hive Energy, a British renewables energy company, and a $1bn greenfield project by Vantage Data Centers, a US IT services management company, to build its first African campus.

Investment flows to Mozambique grew by 68% to $5.1bn during 2021. The country saw a jump in greenfield projects, including UK-based Globeleq Generation’s plan to build power plants for $2bn.

Nigeria, Africa’s biggest economy and West Africa’s largest recipient of FDI, saw its flows double to $4.8bn in 2021, mainly because of a resurgence in investments in the oil and gas sectors. International project finance deals in the country jumped to $7bn. These included the $2.9bn Escravos Seaport project to construct an industrial complex.

Projects in extractive industries also helped push FDI to Ghana up to $2.6bn – an increase of 39% compared with 2020. Senegal also saw a notable 21% increase in FDI, which reached $2.2bn. The country registered a 27% rise in announced greenfield projects.

Ethiopia could attract a lot more FDI in the future

Ethiopia – a central hub for China’s Belt and Road Initiative – saw FDI flows rise by 79% to $4.3bn in 2021. Four out of five international project finance announcements in the country were in renewables. Investment flows to Morocco jumped by 52% to $2.2bn in 2021, while Egypt saw its FDI drop by 12% to $5.1bn. Despite the decline, Egypt was Africa’s second-largest FDI recipient after South Africa.

Pledges from Gulf states to invest around $22bn in a number of economic sectors in Egypt could boost FDI in the future. Furthermore, announced greenfield projects in the country more than tripled to $5.6bn in 2021.

“I think Ethiopia could receive a lot more FDI during 2023,” says Matshego. “Currently, it has the greatest potential of any African country in FDI terms. A peace deal has now been signed between the government and the Tigrayan rebels, and the government is trying to open up the country further in many ways. Very big investments in the country’s textiles sector have been taking place and should continue. The government is also considering reforming Ethiopia’s banking sector. However, the security situation will remain prominent and the country’s stability remains fragile.

“On the other hand, Nigeria’s FDI outlook remains dependent on the outcome of the presidential elections there [in February 2023]. However, I think the investment climate will remain more or less the same. The country has very complicated social and political systems and it is hard to see the economy shifting towards liberalisation.”

Despite the overall positive FDI trend on the continent, total greenfield announcements remained low at $39bn in 2021, showing only a modest recovery from the $32bn recorded in 2020 and way below the $77bn registered in 2019.

The largest holders of foreign assets in Africa remained European, led by investors in the UK ($65bn) and France ($60bn).

Africa now has world’s biggest free trade area

The African Continental Free Trade Area (AfCFTA) – the world’s biggest free trade area that encompasses 54 of Africa’s 55 countries – went live on 1 January 2021. It could be an economic game changer. Only 18% of all Africa’s commerce is intra-African trade, while the equivalent figure in east Asia is between 35% and 40%. Africans trade more with the rest of the world than they do among themselves.

The AfCFTA could present significant opportunities for increased FDI into the region in the future. By reducing tariff and non-tariff barriers to trade, investors in one member state could have access to an expanded market for goods and services across Africa. Intra-African investment, an increasingly important source of FDI, could also improve under the AfCFTA.

Investors in South Africa, Mauritius, Kenya, Togo and Nigeria accounted for more than 75% of intra-Africa FDI between 2014 and 2018, although investment funds from Mauritius may represent investments from other sources channelled through the country to benefit from its favourable taxation policies.

Africa’s share of global FDI has been low and stagnant over the past decade. African FDI inflows averaged 3% of the global total between 2014 and 2018 and 2% in terms of total accumulated investment (inward FDI stock), according to the US Department of Agriculture. China is a leading source of greenfield FDI in Africa, investing more than $71bn (494.91bn yuan) between 2016 and 2020. During the same period, the US invested only $23bn.

Among the top 30 African destinations for FDI, the four countries with the largest average annual FDI stock values are Mauritius, South Africa, Nigeria and Egypt. Together, they accounted for almost 65% of FDI stock on the continent between 2014 and 2018.

Sub-Saharan Africa’s economic recovery was interrupted abruptly in 2022. In 2021, the region expanded by 4.7% but, in 2022, it was expected to grow by only 3.6% and is forecast to expand by only 3.7% in 2023, according to the International Monetary Fund. The year 2022 was another challenging one for Africa and many African countries have become a lot more indebted. The region has immense potential to attract greater amounts of FDI, but that may have to wait until the global economy picks up again and the AfCFTA is fully implemented.

Source : Investment Monitor