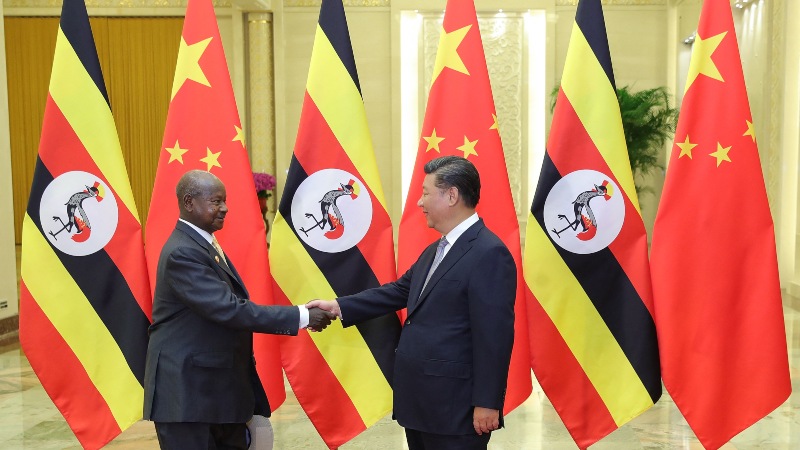

‘Ugandan Agency within China-Africa Relations: President Museveni and China’s Foreign Policy in East Africa’ is an analysis of power relations between China and Uganda under President Yoweri Museveni.

The book by Barney Walsh was published by Bloomsbury in 2022. It mainly covers the period from 2000 to 2015 and argues that relations between China and Uganda, and by extension other African countries, have too often been analysed solely in terms of Chinese strategy, with insufficient regard being paid to African agency in the relationships.

The book argues that Chinese support has enabled Museveni to strengthen his position with the East African Community and to contribute to regional and Western security. Museveni is “the region’s elder statesman whose longevity in power carries significant clout”. Indeed there are real achievements to point to, such as Museveni’s anti-terrorism record and his chairmanship of the regional peace initiative which ended the 1993-2005 civil war in Burundi.

The African sides of relationships with China doubtless need much more attention. But at times, the book supplies it by simply idealising the ability of the “tactically brilliant” Museveni, in power since 1986, to use China for his own ends. Walsh argues that the “shrewd and cunning” Museveni has shown himself capable of “serious, high-level, geopolitical agency” in dealings with Beijing. More widely in Africa, China “provides financial and ideological tools that allow astute, discerning leaders the capacity to impact their domestic and regional environment to a very great extent.”

It seems sufficient to state that Museveni and other African and Asian authoritarians have used their relationship with China as a prop to help stay in power. The key to the success of such relationships, Walsh notes, is Chinese “respect for sovereignty”.

This means that China will not question, and will also aid and abet, the use of force against opponents of the Ugandan or other regimes. Human Rights Watch in March 2022 published a report charging that hundreds of opponents of the Museveni regime have been the victims of enforced disappearances, arbitrary arrests and torture.

Colonialism revisited

Just as European colonialism, whether formal or informal, often had the effect of strengthening the grip of loyalist local elites, modern-day dictators able to access Chinese resources are more likely to retain control. That is hardly surprising and is intended by the Chinese as such: there is little reason for Beijing to invest in political and commercial relationships with identifiably transient regimes.

Historians of European colonialism likewise have a tendency to focus on the local indigenous power elite as a proxy for the colonised society as a whole. The historical sources for colonised elites are usually much easier to find than for other parts of society.

Today, authoritarian rulers dominate the local and international media at the expense of their rivals. Foreign academics and journalists may find themselves on the wrong side of a national argument following regime change. But few are willing to risk losing access to an authoritarian country by criticising its leadership too much.

The book sees oil as crucial to Uganda’s future economic development, and is analysed from the perspective of Museveni’s security and development agendas. A casual reader would not suspect that there are Ugandan civil society groups who are opposed to fossil-fuel projects such as the East African Crude Oil Pipeline (EACOP), or that climate-change impacts may disrupt east Africa’s economy and society more rapidly than in most parts of the world in coming decades. Ugandan opposition to Museveni, the country’s kingdoms and its civil society get thin treatment. The implications of Uganda’s relationship with China for these actors is largely a moot point.

The book, in fairness, does not attempt to assess Museveni’s long rule as a whole. This does make its subjective value judgments more surprising. Walsh notes the use of Chinese anti-riot equipment such as pepper sprayers and water cannons on Ugandan opposition supporters before and after the elections of 2011 and 2016. Yet the West, as Walsh writes, has a “hypocritical” human rights agenda which can make it appear as an “enemy” of Uganda, a failing which China has avoided.

Others would argue that calling out violent human rights violations rather than staying silent is more important than striving for an unattainable absolute moral consistency, and that doing so is a sign not of an enemy, but of a friend.

Source : The Africa Report